It seems straight forward. Anyone who has served in the United States military is also worthy of U.S. citizenship. But it’s not always that easy. In fact, hundreds of U.S. veterans who have served honorably in the armed forces have also been removed from the U.S. Many deported veterans are also separated from their families and their children who live in the U.S. Deported veterans are literally accumulating across the border in Mexico, hoping that America will give them greater consideration.

Since the Revolutionary War, immigrants have been a vital part of the United States military. In fact, each year about 5,000 non-citizens enlist in the U.S. armed forces. According to the U.S. Defense Department, there are approximately 40,000 non-citizens serving on active duty. More than 4,100 of these dedicated soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in all branches of the U.S. military. Since September 2001, USCIS has naturalized over 130,000 members of the military. The top two countries of origin with immigrants in the military are the Philippines and Mexico.

Many immigrants volunteer for service out of true patriotism. They appreciate the opportunity to live in the United States and want a way to give back. What’s more, immigrants will likely play a larger role in America’s volunteer military in future years.

Immigrants are Vital to the U.S. Military

For the first time since 2005, the Army fell short of its recruiting goal in 2018. That’s only expected to worsen. The pool of candidates for an all-volunteer military is shrinking. In many cases, immigrants are the first to step up and serve.

During Senate testimony in 2006, the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, Marine General Peter Pace, reported that 200 awards or medals have gone to non-U.S. citizens in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that 101 non-U.S. citizens have died in military action since the 2001 terrorist attacks. As the son of Italian immigrants himself, General Pace recognized the sacrifices that immigrants have made to the U.S. military saying that, “[Immigrant soldiers and marines] are extremely dependable … some 8, 9, or 10 percent fewer immigrants wash out of our initial training programs than do those who are currently citizens. Some 10 percent or more than those who are currently citizens complete their first initial period of obligated service to the country.”

RECOMMENDED: Immigrants in the Military

The Number of Veterans Being Deported

No one knows for certain how many military veterans have been deported or ordered removed from the United States. That’s because the U.S. government has failed to track it. There is no electronic system for tracking the veterans that ICE comes into contact with. However, the government admits that approximately 250 veterans were placed in removal proceedings or removed from the United States from fiscal years 2013 through 2018.

Why Veterans are Removed

Veterans are being deported for a variety of immigration violations and criminal offenses. Some individuals served while unlawfully present in America. The U.S. government allowed them to serve, but it wants to remove them afterwards. Other service members may have been arrested for a non-violent crime. In many cases, this stems from drug use.

While serious violent crimes should certainly be considered removal offenses, smaller infractions must be weighed against the total of the circumstances. Military service is a significant factor in weighing in favor of a person’s good moral character. Worse yet, these veterans are rarely given the opportunity to fight deportation.

It’s not a “Trump” problem. In fact, the problem really began under the Clinton administration and has persisted since. The Immigration Reform Act of 1996 made certain crimes deportable. More people became eligible for deportation.

No doubt, the current administration has accelerated this policy. While previous administrations put a focus on violent offenders, the Trump administration has worked diligently to remove any immigrant with a violation or offense, despite family ties or other contributing factors.

Recently, deported veterans were featured in an episode of the Immigration Nation docu-series on Netflix. Cesar, whose parents brought him to the United States as a small child, served in the U.S. marines as a way to serve his adopted country. Despite making the same sacrifices as citizens, undocumented soldiers aren’t afforded the same benefits. When speaking about the United States, Cesar says, “I’m okay to die for it but I’m not okay to live in it.”

ICE Does Not Adhere to Policies for Removable Veterans

Policies are in place that govern the handing of cases involving potentially removable veterans. When enforcement officers learn that they have encountered a veteran, these policies require they conduct additional assessments, create additional documentation, and obtain management approval in order to proceed with the case. According to a recent GAO report, “ICE does not consistently adhere to those policies.” Investigators found that 70 percent of cases involving the deportation of non-citizen veterans didn’t get required reviews. The report also concluded that ICE lacks a policy to identify and document all military veterans it encounters. As a result, many veterans don’t get the additional attention and consideration that they deserve.

Citizenship through Military Service

Naturalization is the process in which a person not born in the United States voluntarily becomes a U.S. citizen. One of the many benefits of U.S. citizenship is protection from deportation. Most deported veterans were eligible for naturalization when they were in the military. Unfortunately, the U.S. government has often failed to prioritize assisting non-citizen service members with completing the naturalization process.

RECOMMENDED: 3 Practical Benefits of U.S. Citizenship That Shouldn’t Be Overlooked

Military Naturalization through Section 328

Under §328 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), immigrants get a special path to citizenship. Generally, an individual in the U.S. armed forces may qualify for naturalization if he or she meets all of the following requirements:

- Must be age 18 or older

- Has good moral character

- Is ready and willing to take an Oath of Allegiance to the U.S. Constitution

- Has the ability to read, write and speak the English language

- Has knowledge of U.S. government and history (civics)

- Obtained lawful permanent resident status before the citizenship interview/test

- Served honorably in the U.S. armed forces for at least one year

- Filed an application while still in the service or within six months of separation

Note that the continuous residence and physical presence requirements typically required for permanent residence is waived. What’s more, the government waives the filing fees.

Expedited Citizenship under Section 329

U.S. President George W. Bush issued an executive order in 2002 that fast-tracked service members’ application for citizenship based on §329 of the INA. Expedited citizenship gives certain military applicants the ability to naturalize immediately during periods of hostility. We are currently in a designated period of hostility (September 11, 2001 – present). The applicant must have served honorably in active-duty status, or as a member of the Selected Reserve of the Ready Reserve, for any amount of time (even one day) during a designated period of hostilities and, if separated from the U.S. armed forces, have been separated honorably. For a service member headed into a conflict, this is significant as it could affect surviving family members.

Declining Naturalizations

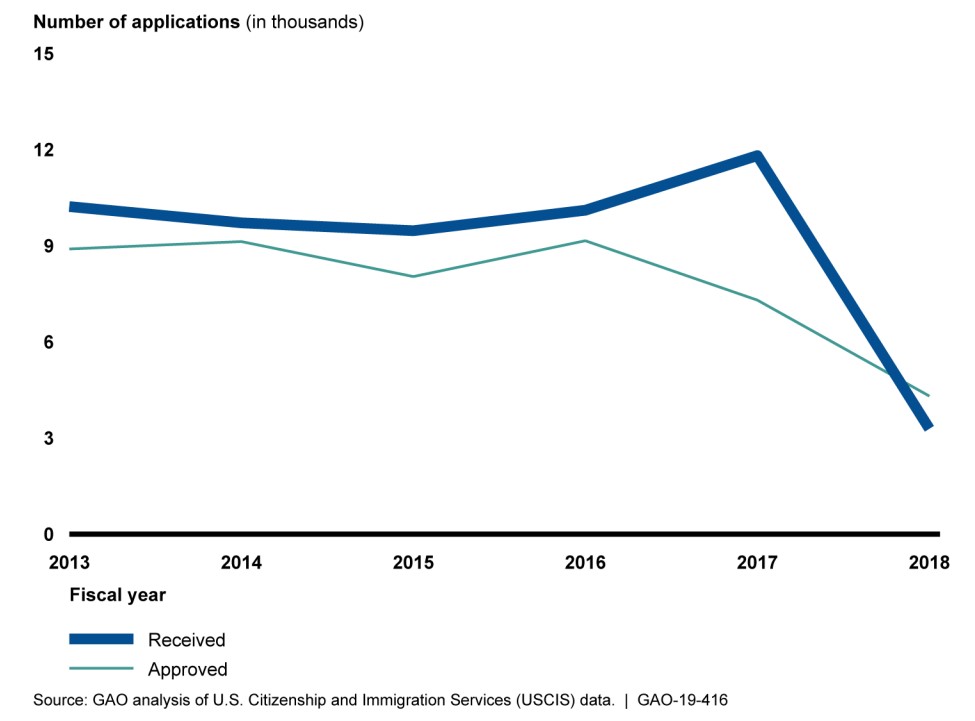

USCIS approved military-based applications for naturalization (Form N-400) at a consistent rate from fiscal years 2013 through 2018. However, USCIS received significantly fewer applications in fiscal years 2017 and 2018. This resulted in a decrease in the number of service members approved for naturalization in fiscal year 2018. From fiscal years 2013 through 2018, USCIS received 54,617 military naturalization applications; USCIS approved 46,835 (86 percent) and denied 3,410 (6 percent).

USCIS and DOD officials attributed the decline in military naturalization applications to various policy changes and phenomena:

- Suspension the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program, a program that encouraged the recruitment of immigrants with certain language and medical skills.

- Expansion of background check requirements for lawful permanent resident recruits. LPRs must now complete a background check and receive a favorable military service suitability determination prior to entering any component of the U.S. armed forces.

- Increased the amount of time non-citizens must serve before DOD will certify their honorable service for naturalization purposes. Under the new policy, non-citizens must complete security screening, basic military training, and serve 180 days for a characterization of service determination.

- Increase in USCIS processing times for N-400 applications.

Veterans Unaware of Naturalization Benefits

Unfortunately, many immigrant service members aren’t even aware of this benefit. According to the ACLU, the majority of deported veterans did not have legal representation. An attorney would ensure that deportation administrators were aware of the individual’s military service. Service in the U.S. armed forces is viewed as a positive factor when determining if prosecutorial discretion should be used. But the ACLU says enforcement officials are not asking about military service.

Deported Veterans Legislation

Army veteran Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-Illinois) has been a consistent advocate for immigrant service members. Last year, she introduced the Veterans Visa and Protection Act of 2019. The proposed legislation would:

- Prohibit the deportation of veterans who are not violent offenders;

- Establish a visa program through which deported veterans may enter the United States as legal permanent residents;

- Enable legal permanent residents to become naturalized citizens through military service; and

- Extend military and veterans benefits to those who would be eligible for those benefits if they were not deported.

Senator Duckworth also introduced the Immigrant Veterans Eligibility Tracking System Act. “Men and women willing to wear our uniform shouldn’t be deported by the same nation they risked their lives to defend,” Duckworth said.

As it is now, many deported veterans must depend on a gubernatorial (governor’s) pardon. Cesar, the veteran featured in the Netflix docu-series, had to seek a pardon for his non-violent drug offense from 2000. His criminal lawyer instructed him to plead guilty to the charge. He paid a fine and wasn’t required to serve any jail time. But immigration law doesn’t always see criminal offenses in the same light. Cesar made a business trip to Costa Rica. Upon reentry to the United States, Customs and Border Protection officers stopped him. They saw has past conviction and subsequently deported him to Mexico, a country he had not been to since he was four years old.

Deported Veterans Support House

An unofficial refuge has emerged in Mexico to help some of these deported veterans. The Deported Veteran Support House is a shelter in Tijuana, Mexico, just across the border from San Diego. As the problem persists, the number of veterans deported from the U.S. grows. As you thank veterans for their service and sacrifice this year, consider donating to the support house and asking your local representative take action on this problem.

About CitizenPath

CitizenPath provides simple, affordable, step-by-step guidance through USCIS immigration applications. Individuals, attorneys and non-profits use the service on desktop or mobile device to prepare immigration forms accurately, avoiding costly delays. CitizenPath allows users to try the service for free and provides a 100% money-back guarantee that USCIS will approve the application or petition. We provide support for Adjustment of Status (Form I-485), the Citizenship Application (Form N-400), Green Card Renewal (Form I-90), and several other immigration services.

The post Deported Veterans Deserve a Fair Shake at U.S. Citizenship appeared first on CitizenPath.

from News | CitizenPath https://ift.tt/2DrIna6

via Dear ImmigrantDear Immigrant